Random to Habituated Behavior

Curator’s note: the following is from an Autonomist forum discussion.

by Reginald Firehammer

Hi Cass,

Thank you for pointing out some obvious ambiguities in the discussion of consciousness I need to make clearer and more explicit.

The first is one about the nature of consciousness itself. I’ve tried to be very careful about this, but apparently not careful enough.

You said, very early in this thread:

It is taught as an absolute that mankind protects himself, feeds himself and reproduces, because we are like any other animal, and are driven by Mother Nature to maintain the species. And no-one stops to notice that other specie, thousands of them, are all doing this very successfully without consciousness (I am differentiating here between consciousness and levels of perceptual awareness, which animals have in varying degrees).

In your last post you said:

Volition, in your model so far Regi, seems to act as a superior level of consciousness, a higher order so that one can almost diagram (I lack this skill, along, alas, with so many other computer skills) a pyramid, with passive, generalized perception at the base, the conscious experience above that, and RHB above that with volition above all.

What I am about to say pertains to consciousness itself, which was the original issue of this whole thread. It is the very question you are asking I know is so common that I wanted to clear up. I very much appreciate your making the areas I’ve left unclear specific.

There are not different kinds or levels of consciousness. Perception is the only kind of conscious there is in either man or animals. Consciousness is perception.

There is no difference in kinds of consciousness. Humans and animals have essentially that same kind of consciousness, perception. There are obvious difference in the nervous systems of various species which will result in varying degrees of acuity in eyesight, hearing, sensitivity to temperature, etc. which will obviously cause variations in what an animal can be conscious of—but the consciousness in all animals is perception. All animals perceive and only perceive whatever its nervous system and memory present to it.

Consciousness is entirely passive. It merely observes, or is aware of, or perceives whatever is presented to it. Volition is not an aspect of consciousness. The relationship between volition and consciousness is twofold: using choice in the broadest sense (because technically it pertains only to conceptual choice), 1. volitional choice can only be made about that of which one is conscious, and 2. one is conscious of all volitional choice. Consciousness is, therefore, a necessary prerequisite for volition, but technically it is a mistake to call consciousness volitional because consciousness is only the awareness or perception and nothing more.

Now, the specific questions you asked.

One, concerning your RHB. You state that it is (a) part of consciousness, which is not physical, yet also that (b) it comes pre-programmed.

I thought I made it clear that RHB is not part of consciousness. What I did say that may have given you that impression is that we are conscious of RHB’s function, just as we are conscious of our hand’s function, but neither our hands or RHB are part of consciousness.

I also said the RHB is pre-programmed in the instinctual animals, but is definitely not pre-programmed in man. (Technically the animals do not have RHB, which means random to habituated, and is meant to indicate those functions which, in man, at birth are capabilities or potentials, but tabula rasa and must be programmed volitionally. Once programmed, they are automated (habituated), but can always be volitionally controlled when necessary.

However, this also gives rise to the question; are you saying animals, (at least higher order mammals) are not able to exercise choice when faced with two possibilities?

There is both a semantic problem and a conceptual problem here, I think. I obviously have not made these concepts clear enough, and I’ll attempt to do that once and for all.

The semantic problem is in the use of the word choice. In the general use of the word, it applies to every case where more that one action is possible, but not both. In that general sense, everything any living thing does is a choice. Every step an animal takes is a choice, because it could have stepped or not stepped. We even use the word about physical behavior, which in the general sense of the word is perfectly correct, even when we know that choice was physically determined. The semantic confusion comes from the fact we are not careful to distinguish between the general use of the word choice and the specific meaning choice has when we are talking about human volition. This confusion is possible because the meaning of volitional choice is not well conceived either.

The mistake, I think, comes from assuming that any action that is a result of choice in the general sense where there is consciousness is in some sense volitional. But this is not true at all.

The Decision Tree

To explain, I will use an analogy from computer programming. There is programming method called a decision tree used in some programs which enable it to perform different functions depending different conditions. Decision trees can be implemented in a number of different ways, but I will use a very simple example.

Our decision tree will be used to control a lawn watering system. The conditions are as follows:

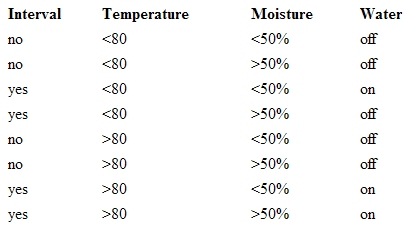

The program has three inputs, an interval timer, a thermometer, and a soil moisture detector. The program will check the interval timer each hour. If the interval timer is set to yes, the program will check the temperature and soil moisture. Depending on the conditions the program will or will not turn on the lawn sprinklers. The conditions are provided in the following table. [The interval timer is preset to 4 hours, no under this heading means the timer is not reached its next interval when checked, and yes means it has. < 80 means less than 80 degrees, >80 means greater than 80 degrees. off under the Water heading means the sprinklers are not turned on, and on means they are.]

The table shows all 8 possible conditions for each of the three things (interval, temperature, and moisture) that determine when the sprinklers are turned on. A brute-force program might just store each of the 8 combinations and do a comparison for the decision. A more elegant and efficient way is to use a decision tree, as in the following figure:

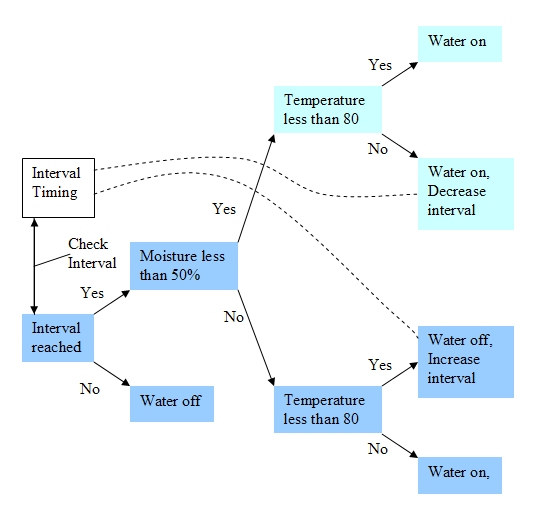

The advantage of the decision tree is that instead of comparing 8 possible states, a maximum of three states need to be checked. As an illustration of choice the program chooses to turn the sprinklers on or not based on the conditions the input sensors indicate exist. This simple program illustrates non-volitional choice. But we need one more factor for the analogy to be complete.

We may be dissatisfied with the way this program keeps the grass watered. It might be necessary to alter at certain times to make the interval between waterings longer or shorter. Another way would be to make the program alter itself. By allowing some conditions to increase the interval, and other conditions to decrease the interval, the program can learn how to behave under different conditions. Here are the conditions:

The decision tree that will perform both the decision making and the learning is illustrated in the following figure:

There is no level of sophistication in both complexity of decision or choice or learning that such a scheme cannot achieve. However complex or sophisticated such a program is, the decision (or choices) made, are determined—not volitional.

Instinct—The Animal’s Program

There is one distinction between the computer program analogy and animal behavior however. Animal’s do have consciousness, just like human consciousness, with two exceptions—what they are specifically be conscious of depends on their specific nervous system, and how they react to the content of consciousness is determined by that program which we call instinct. While they are conscious of their own behavior (which includes their, learning, and the decisions their instinct makes) they cannot choose not to act instinctively.

The point of the illustration is to demonstrate that non-volitional decision making is capable of both behavior and learning of unlimited complexity. A programmed behavior, however, cannot be a mixture of volition and program because it would require a break in the function of the instinctive program. Instinct is the means of survival of all animals but man—anything that interfered with that program (volition, for example) would essentially cancel it, or at least cripple it, thus crippling or making it impossible for the animal to survive. It is precisely because man does not have any pre- programmed patterns of behavior he is able, (and required) to form concepts, that is, to identify consciously what he perceives, and discover the nature is of those things he perceives and how he ought to behave to survive.

A note about the relationship between RHB and Instinct—At birth, human infants do not have the ability to do anything specific. They must learn and develop everything, from hand-eye coordination, to walking. An animal, from birth, or within hours of birth when all it’s physiological functions are established, already has complete control of all its functions. In the early stages of development, the progress from random to habituated behavior in the human child develops many of the same kinds of behavior which come pre- programmed in animals; behavior which the animal does not have to think about and does automatically. RHB, when developed, provides a similar function in humans—it provides automatic behavior that one does not have to think about. The important distinction is, a human can think about that behavior and can at any time, volitionally override RHB behavior—an animal cannot override its instinct.

Regi